By Associate Professor Louise Smyth

Published September 2021

Allergy is clinically, economically and socially important. It is common, may be life-threatening and results in lost school or work attendance. Furthermore, it can be intensely unpleasant for the patient.

Immune responses

Immune responses represent a continuum of protective strategies that have developed from very ancient needs. As multicellular, and then vertebrate, animals evolved, systems were required that could sustain, control and protect parts that are not directly contiguous with sources of energy production (nutrients, oxygen) nor able to directly remove wastes. All of these systems required a structural base and a rapid response mechanism. The outcome was a circulatory system, nervous and endocrine systems and the immune system. Each functioned through intimate, two-way interaction with the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, blood and genitourinary tract.

Protection of the complicated and expanded organism extended mechanisms used by single-celled organisms, biofilms and simple multicellular organisms, as well as some of the cellular interaction tools of invertebrates. Adaptive, or learned, immunity developed alongside the vertebrate nervous system and was supplementary to, augmenting, and dependent upon earlier mechanisms that largely comprise the innate immune responses.

Innate immunity continues to contribute barrier responses on skin and mucosal surfaces where the vertebrate organism’s frontier is both exposed to danger and sources its supplies. It provides the earliest responses to colonisation of surfaces or invasion of tissues and it samples foreign material for assessment and response by the adaptive, lymphocyte-based, immune response. Critically, the acute inflammatory response of innate immunity both transports and presents foreign material to lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid tissue (lymph nodes, spleen, MALT, SALT), and carries accompanying coded messages that indicate the presence or absence of tissue damage. Thus, an adaptive immune response is generated by two distinct signals that define threatening non-self. Thirdly, the detailed milieu of the self/nonself-interaction generates differing chemical messaging via informative combinations of secreted cytokines that guide the direction of that response. These responses are predicated upon cells of innate immunity, in the form of Antigen Presenting Cells (APCs), engaging those of adaptive immunity.

Adaptive immunity is characterised by its anamnestic nature. Not only is the cause of the response (antigen or allergen) remembered, but also the result of the first encounter. Following, and dependent upon, the innate response to damage, there is a combined T cell and B cell response whereby lymphocytes are engaged in maturation pathways that lead to the eradication of the threat.

Antigens that can be engaged in the extracellular space can be dealt with by a coterie of soluble proteins, based upon the specificity of the B cell product: immunoglobulin. Which sort of immunoglobulin is directed by Helper T cells with differing profiles.

Intracellular pathogens require a response that kills the host cell. These pathogens require a cytotoxic T cell response.

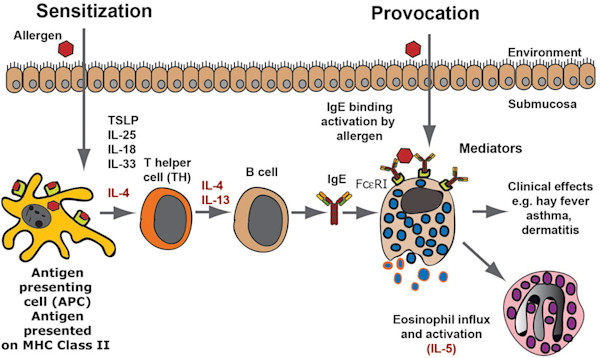

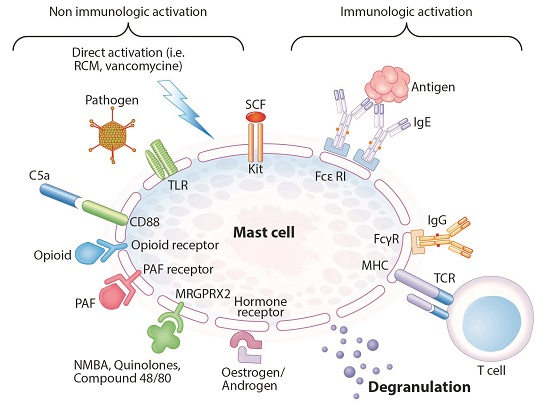

Other pathogens exist primarily on the mucosal surfaces and are too big or unavailable for phagocytosis by cells of the innate response, e.g. helminths. For these, the adaptive immune response has developed an extracellular response dependent upon releasing pre-formed inflammatory (innate) mediators, directly onto the offending agent. This is driven by TH2 type T cell help directing B cell immunoglobulin class-switching to IgE production and is achieved by pre-engaging the responding cell (mast cells) by IgE bound to its membrane receptor FcεRI. Crosslinking of membrane bound specific IgE by its recognised (cognate) antigen results in mast cell degranulation, releasing packets of pro-inflammatory mediators. These cause local inflammation. Basophils and eosinophils are also involved in this response (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An allergic immune response. The figure presents a schematic overview of an allergic immune response starting with the allergens first contact when it enters through the skin, lungs or intestinal mucosa. Antigen-presenting cells, primarily dendritic cells, take up the antigen and process it into peptides, which are subsequently presented to naïve T cells. These T cells produce IL-4 and IL-13, which stimulates B cells to switch to IgE production. The IgE produced by these local B cells binds tissue mast cells, which have now become sensitised and can respond by degranulation as well as prostaglandin and leukotriene synthesis, which provides all the symptoms of an allergic reaction. As a next step, locally produced IL-5 results in eosinophil influx and the induction of a late phase response. (Caption abbreviated). (Hellman, et al., 2017).

T cell help for B cells not only directs the subsequent immune response but also results in a small proportion of educated B cells converting to memory cells. These cells are on shortened pathways of specific recognition and response and are the basis of immune memory and avoidance of disease upon subsequent exposure, the secondary immune response. This response is further characterised by higher levels of class-switched antibody production and antigen receptor editing that results in increased affinity and avidity. Therefore, the secondary immune response resembles a clever Olympic athlete; it goes higher, stronger and faster and has an impeccable memory.

Hypersensitivity, allergy and intolerance

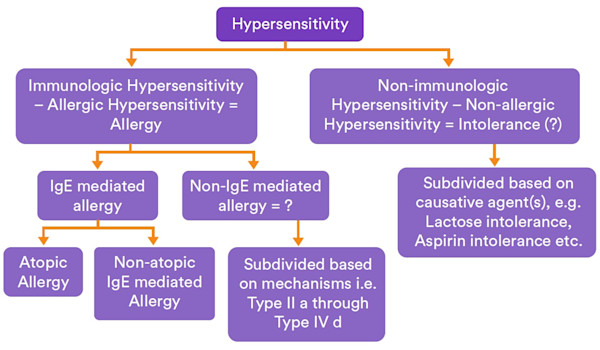

Hypersensitivity reactions are those immune responses that result in tissue damage that is disproportionate to their defence function because they are excessive or inappropriate. In 1963, Gell and Coombs first published their seminal “Classification of allergic reactions underlying disease” that, although revised and modified by later authors, formed the basic approach to the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in both allergy and autoimmunity. The original classification designated IgE mediated, immediate hypersensitivity responses as Type I responses. These are the classical allergic responses. Since then, some drug and food allergies, eczematous dermatitis and chronic hypersensitivity responses (such as chronic urticaria, asthma, chronic rhinitis, Eosinophilic Oesophagitis) have been shown to represent complicated and overlapping immune responses that may, or may not, be easily assessed in the routine laboratory (Figure 2). Importantly, more than one allergic disorder may exist in the same patient. Associated disorders, such as nasal polyps, are outside the scope of this article.

Figure 2. Illustration of proposed minor changes of the food hypersensitivity nomenclature, using “intolerance” as short for “non-allergic hypersensitivity”/“nonimmunological hypersensitivity”. Dreborg, S. World Allergy Organization Journal (2015).

Figure 3. Immunologically and non-immunologically induced mast cell degranulation (adapted from Hannino et al.). Abbreviations: RCM: radiocontrast media, TLR: Toll-like receptor, SCF: Stem cell factor, FcεRI: high affinity IgE receptor, FcγR: IgG receptor, TCR: T-cell receptor, NMBA: neuromuscular blocking agent, PAF: platelet activating factor, MHC: major histocompatibility complex. (Spoerl, et al., 2017).

Furthermore, some clinical mimics or similarities may make assessment difficult (e.g. hereditary angioedema vs urticaria) and some clinical manifestations may have “allergic” and “non-allergic” aetiologies. Allergy, however, is perhaps the most deserving clinical state for the aphorism: listen to the patient for long enough and they’ll tell you the diagnosis. Intolerance should, strictly, be reserved for those clinical manifestations that do not have an immunologic pathogenesis, e.g. lactose intolerance due to decreased enzyme activity.

Therefore, symptoms and signs induced by a specific agent can be described as immune (allergic) or nonimmune hypersensitivity responses and, immune hypersensitivity responses as Type I/Immediate/IgE mediated or non-IgE mediated allergic responses.

Looking at allergy in routine clinical practice

All secondary immune responses are a response to previous exposure, including allergy, although that exposure may be difficult to identify (e.g. food allergens in infants/toddlers). Hence, the exposure history is usually centred on the clinical manifestation of allergic (or possible allergic) symptoms and signs. These may be obvious, particularly with food allergy where oral symptoms may arise within seconds to minutes following exposure (oral allergy syndrome – OAS), or they may require more, or less, detailed examination of the environment. Some simple approaches may be useful in persons with limited allergies: pollens are prominent outdoors in spring and summer, moulds – indoors especially in winter (but possibly perennial), house dust mite indoors and all year, animal dander following specific exposures, etc. It is also true that there are many “overlapping” allergies due to the fact that the allergen is often a highly conserved, shared peptide in related species, e.g. certain foods, pollens, insects, etc. This information is important in selecting laboratory testing of specific IgE, which can be used to manage, by avoidance or immunotherapy, severe or nuisance allergies. Other important tests may include eosinophil count (or activity) but testing should have a focus that is relevant to the symptoms produced after a timely exposure history.

Both skin prick testing (SPT) and serum specific IgE (previously RAST) are useful for identifying the presence of allergen-specific IgE in a given patient and are useful in assessment of allergic rhinitis. However the presence of antibody does not equal disease and results must be interpreted in the clinical context.

Common respiratory allergens

- House dust mite

- Pollen

- Animal dander

- Mould

Food allergens

Food allergens present several diagnostic difficulties, partly because only certain foods/components are mandated in labelling by Australian food standards and partly because of “unseen contamination”, e.g. during food preparation. Furthermore, some non-food items (e.g. cosmetics) may contain food allergens. Food ingestion may result in a variety of clinical manifestations ranging from OAS through skin reactions to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Most food allergens are primarily managed by avoidance but diets can be restrictive and so it is important to correctly identify the relevant allergen. According to current information ASCIA states that food allergy occurs in around 2% of Australian and NZ adults with increased numbers in childhood, up to about 10% of infants. Again, SPT and specific IgE are useful for identifying the presence of allergen-specific IgE in a given patient, although SPT may be impractical in young children. Elimination diets and challenge may be required but should be conducted under specialist advice/supervision. A recent review by Eckman demonstrates the strong positive predictive values of serum specific IgE for certain food allergy diagnosis for atopic dermatitis in children (Table 1).

Common food allergens

- Egg

- Cow’s milk

- Peanut

- Tree nuts

- Sesame

- Soy

- Fish

- Shellfish

- Wheat

Some less common food allergens, such as red meats, may be clinically important.

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs)

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are probably the most complex clinical event requiring consideration of an allergic response. ADRs are classified Type A if they are predictable due to the known properties of the drug and Type B if they are unpredictable or idiosyncratic. Type B reactions include allergic reactions that may be IgE mediated immediate responses, including anaphylaxis, or several cell-mediated immune responses. The clinical history is crucial in assessing drug reactions of all types. While serum specific IgE is available in the investigation of many potential drug allergies, specialist clinical assessment may be required. It is important to consider de-labelling of some patients who believe that they are penicillin-allergic, since potentially important therapeutic interventions may be unnecessarily curtailed.

Insect venoms

Insect venoms are an important cause of allergy including anaphylaxis. Specific IgE is available for most clinically important insect venoms. Other insect allergens may cause respiratory or skin symptoms and assessment can also be assisted by serum specific IgE.

Other in-vitro tests that may be used in the investigation of allergy include mast cell tryptase (obtained within 6hrs of possible anaphylaxis, preferably 1-2hrs) and serum complement. Allergic urticaria is usually of shorter duration than that associated with autoimmune disorders.

Some cases may be assisted by detection of serum specific IgE. Latex and contact allergies, such as nickel, are frequently assessed by clinical investigation.

Useful and updated guidelines for the clinical management of allergy are available from the ASCIA website (www.allergy.org.au).

Table 1. Comparison of studies reviewing the positive predictive values of food specific IgE testing. Adapted from: Diagnostic evaluation of food-related allergic diseases (Eckman, et al., 2009).

| Study | No. subjects | % Atopic dermatitis | Food | PPV value %/ Specific IgE level | Sens. for IgE level | Spec. for IgE level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampson HA | 62 | 61% | Cow's milk | 95%/15 | 57% | 94% |

| Sampson HA and Ho DG | 196 | 100% | Cow's milk | 95%/32 | 51% | 98% |

| Celik-Bilgili S et al | 398 | 88% | Cow's milk | 90%/88.8 | * | * |

| Garcia-Ara C et al | 170 | 23% | Cow's milk | 95%/5 | 30% | 99% |

| Osterballe M et al | 56 | 100% | Egg white | 100%/1.5 | 60% | 100% |

| Boyano Martinez T et al. | 81 | 43% | Egg white | 94%/0.35 | 91% | 77% |

| Celik-Bilgili S et al. | 227 | 88% | Hen's egg | 95%/12.6 | * | * |

| Sampson HA and Ho DG | 196 | 100% | Hen's egg | 95%/6 | 72% | 90% |

| Sampson HA | 75 | 61% | Hen's egg | 98%/7 | 61% | 95% |

| Sampson HA | 68 | 61% | Peanut | 100%/14 | 57% | 100% |

| Sampson HA and Ho DG | 196 | 100% | Peanut | 95%/15 | 73% | 92% |

| Maloney JM et al | 234 | 57% | Peanut | 99%/13 | 60% | 96% |

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our electronic Pathology Focus newsletter.

How to Order Allergen-Specific IgE Testing

Complete a Clinical Labs General Pathology Request Form, specifying serum-specific IgE testing. To indicate the specific allergens or mixes required, use the Allergen-Specific IgE Order Form.

Please be as specific as possible in your selections, based on the patient’s detailed clinical history.

Blood samples can be collected at any Clinical Labs collection centre.

Please note:

Allergen mixes are best used to refine the direction of individual allergen requests, which have better sensitivity and specificity prior to treatment.

In children, due to lack of sensitivity and specificity, and to prevent unnecessary food avoidance, testing for individual allergens is preferred over mixes.

When one penicillin allergen is ordered for sensitivity testing, such as Amoxycillin, Clinical Labs will routinely test all four available penicillins individually as standard practice.

Medicare will fund up to four patient episodes of Allergen-Specific IgE testing within any 12-month period. Each episode may include four single allergens, four allergen mixes or any combination of four allergens and mixes. If tests are not ordered together, each additional episode will require a new referral and specimen collection. Any tests requested beyond this limit will incur an out-of-pocket cost to the patient.

Test requests beyond this limit will incur an out-of-pocket cost to the patient of $15 per individual allergen or allergen mix.

References

Gell, P. G. H. & Coombs, R. R. A. (1963). Clinical aspects of immunology. 1963 Blackwell Scientific. Oxford.

Hellman Lars Torkel, Akula Srinivas, Thorpe Michael, Fu Zhirong. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017, Vol. 8, p1749. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01749

Spoerl D, Nigolian H, Czarnetzki C, Harr T. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017, 18(6):1223. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18061223

Eckman, J. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 2009, 5:2 doi:10.1186/1710-1492-5-2 http://www.aacijournal.com/content/5/1/2

Dreborg, S. World Allergy Organization Journal (2015) 8:37 http://doi:10.1186/s40413-015-0088-6

Australian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy www.allergy.org.au