A modern diagnostic perspective

By Associate Professor Louise Smyth

Published December 2020

Chronic, diarrhoeal disease of unidentifiable aetiology is described as early as ancient Greek medical tracts and, in retrospect, both Fabry and Morgagni probably describe cases prior to Matthew Baillie’s 1793 report of lethality of an ulcerative colitis. Following that description, many of the chronic diarrhoeal disorders of unknown aetiology were described as ulcerative colitides. After the description by Sir Samuel Wilks, in 1859, of the autopsy changes found in a 42-year-old woman who died after several months of intractable diarrhoea and fever, the term gained prominence. When Sir William Hale White published a series of cases in 1888, “Ulcerative Colitis” (UC) entered the lexicon. However, a review of Wilks’ case using modern diagnostic criteria, would prefer Crohn Disease (CD) but the seminal paper of Burrill Crohn, that differentiated his eponymous, idiopathic, chronic inflammatory disease of the bowel wall, with extra-enteric involvement, did not appear until the October, 1932, edition of JAMA, just 88 years ago, despite several earlier references to the differing patterns of disease and associated pathological findings. Nevertheless, the clinical presentation may not always be clear, especially during the first months of symptoms, and some cases may remain as undifferentiated colitis while others are otherwise resolved. The association between UC and colorectal carcinoma had already been reported, following the introduction of safe sigmoidoscopy, in 1909 by John Lockhart-Mummery (Mulder, Noble, Justinich, & Duffin, 2014).

The mean Australian annual incidence rate for IBD reported to EpiCom (European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization– Epidemiological Committee) in two independent cohorts from 2010 and 2011 was 30.3/100,000 (Vegh. et al. 2014). The prevalence in Australia is expected to increase by approximately 250% from 2010 to 2030. Furthermore, while still predominantly a disease affecting young adults, where the incidence may be reaching a plateau in Western countries (Weimers & Munkholm, 2018), both paediatric and elderly patients are increasingly being diagnosed (Gower-Rousseau, et al., 2013). In addition, these special groups and others may present with different disease phenotypes and require different treatment regimens. In this Northern French population, of similar size to that of Victoria, the incidence rate of CD increased from 5.3 to 7.6 per 105 over the study period (1988-2008) while UC remained stable. Strikingly, the incidence of CD in patients under 20 years old nearly doubled, a finding replicated in Italy, Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia. Importantly, the extent of disease and the inflammatory phenotype was shown to be more severe in younger patients. In fact, the Montreal criteria for the evaluation of adult IBD has been supplemented by the Paris criteria for paediatric disease.

Table 1 - Montreal and Paris Classifications for Crohn’s Disease (CD)

| Montreal | Paris | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | A1: < 17 y A2: 17-40 y A3: > 40 y | A1 a: < 10 y A1 b: 10-17 y A2: 17-40 y A3: > 40 y |

| Location | L1: Terminal ileal ± limited cecal disease L2: Colonic L3: Ileocolonic L4: Isolated upper disease* | L1: Distal 1/3 ileum ± limited cecal disease L2: Colonic L3: Ileocolonic L4 a: Upper disease proximal to Ligament of Treitz* L4 b: L4b: Upper disease distal to ligament of Treitz and proximal to distal 1/3 ileum* |

| Behaviour | B1: Non-stricturing, non-penetrating B2: Stricturing B3: Penetrating P: Perianal disease modifier | B1: Non-stricturing, non-penetrating B2: Stricturing B3: Penetrating B2B3: Both penetrating and stricturing disease, either at the same or different times P: Perianal disease modifier |

| Growth | n/a | G0: No evidence of growth delay G1: Growth delay |

*In both the Montreal and Paris Classification systems, L4 and L4a/L4b may coexist with L1, L2, L3, respectively.(After Levine et al., 2011)

Table 2 - Montreal and Paris Classifications for Ulcerative Colitis (UC)

| Montreal | Paris | |

|---|---|---|

| Extent | E1: Ulcerative proctitis E2: Left-sided UC (distal to splenic flexure) E3: Extensive (proximal to splenic flexure) | E1: Ulcerative proctitis E2: Left-sided UC (distal to splenic flexure) E3: Extensive (hepatic flexure distally) E4: Pancolitis (proximal to hepatic flexure) |

| Severity | S0: Clinical remission S1: Mild UC S2: Moderate UC S3: Severe UC | S0: Never severe* S1: Ever severe* |

*Severe defined by Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) ≥65.(After Levine et al., 2011)

In this French, community-based study, the increased severity of early onset disease was evident despite greater use of immune suppression and biological anti-inflammatories, in this group.

“ … clinical symptoms on diagnosis were more subtle in the elderly than in the younger age groups with less diarrhoea, abdominal pain, weight loss, fever and extra-intestinal manifestations (EIMs) in CD and less rectal bleeding and abdominal pain in UC. … As for phenotypes, elderly onset CD was characterised by the predominance of pure colonic disease (L2) and inflammatory behaviour (B1) in accordancewith the literature and in sharp contrast with the youngest age-group. On the other hand, UC location on diagnosis was more alike in the young-onset and elderly onset groups with more extensive disease than in the middle-age group.” (Gower-Rousseau, et al., 2013)

In the same study there was significantly more disease extension, stricturing and perforating behaviour in patients <17 years at diagnosis compared to those >60 years.

Elsewhere, an association with Primary Immune Deficiency (especially NOD2 gene & IL10 pathway) has been established in up to 20% of children with very early onset disease (<5 years) and these children should be assessed by a paediatric Clinical Immunologist (Kelsen & Sullivan, 2017). In all age groups, intestinal infection should be excluded as a cause of presenting symptoms, especially in high-risk groups but, infection is also an important complication of IBD (especially penetrating CD) and presents a risk to patients who require immune suppression.

While the aetiology and pathogenesis of IBD remains unclear, it is ever more clear that they represent a complex interaction of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors resulting in abnormal immune responses directed against the gut microbiota of affected individuals. The changing epidemiology, detailed by Kaplan and Windsor (Kaplan & Windsor, 2020), underlines the association with increasing Westernisation/industrialisation. Diagnosis is predicated upon endoscopy, imaging and histology butfeatures may change in serial small biopsies of bowel and a significant proportion of diagnoses are only secured after colectomy. Selection of patients for diagnostic endoscopy or follow-up assessment of disease activity can be enhanced by the measurement of blood and faecal biomarkers, which may also favour one disease over the other, minimising expensive, invasive, higherrisk investigation. It is especially useful to identify patients without evidence of bowel wall inflammation at presentation, who are more likely to have Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). The usefulness of biomarkers has been established in adults (Kochhar & Lashner, 2017) and in children (Elitsur, Lawrence, & Tolaymat, 2005).

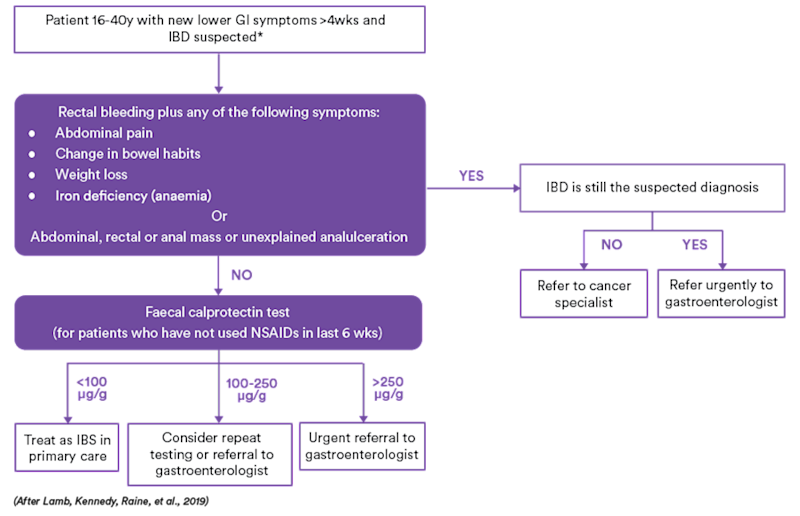

UK Guidelines suggest the following approach to differentiate patients presenting with symptoms that may be attributable to IBD or IBS.

Figure 1. Use of Faecal Calprotectin Test in Primary Care.

Table 3 . Usefulness of tests available at Clinical Labs for the assessment of possible or established IBD, other than biopsy.

| Biomarker | Source | Clinical Use | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute phase reactants | ||||

| CRP | Blood | General measure of systemic inflammation. CRP increased in most with active inflammation. CD > UC. | High | Low |

| ESR | Blood | General measure of systemic inflammation. ESR peaks and decreases slower than CRP. May be better at monitoring disease activity/response to treatment after the first 24 hours of onset while CRP may be more useful in the first 24 hours. | High | Low |

| Antibodies | Best used in combination. | |||

| Anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) | Blood | Adults and children with CD. | Low to moderate | Moderate to high |

| Anti-perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) | Blood | Adults and children with UC. | Moderate to high | Low to moderate |

| ASCA+/pANCA- | Blood | Favour CD in clinical IBD. | Moderate | High |

| ASCA-/pANCA+ | Blood | Favour UC in clinical IBD. | Moderate | High |

| Calprotectin | Faeces | IBD versus IBS. Activity of IBD & postoperative recurrence of CD. | High | Moderate. Measures granulocyte-mediated inflammation in the bowel wall. RI varies by age in children. |

Follow-up on Coeliac Disease (CD) Testing

Once a proband has been identified it is important to screen asymptomatic first-degree relatives (or other close relatives who may have symptoms). There are two schools of thought regarding the best screening of first degree relatives. Initial screening for susceptibility by HLA DQ2/8 identification has been shown to be cost-effective compared to repeated autoantibody testing and endoscopy for asymptomatic individuals. HLA DQ testing is done once and patients who have neither antigen should only be further investigated for CD under specialist management.

The European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) has issued guidelines, updated in 2019. According to their recommendations:

- If CD is suspected, measurement of total serum IgA and IgA-antibodies against transglutaminase 2 (antitTG) is superior to other combinations.

- If total IgA is low/undetectable, an IgG based test is indicated. (ACL routinely tests for IgG antibodies against deamidated gliadin peptide for initial testing.)

- If anti-tTG -IgA is ≥10 times the upper limit of normal and the family agrees, the no-biopsy diagnosis may be applied, provided endomysial antibodies (EMA-IgA) test positive in a second blood sample and patients with positive results have been referred to a paediatric gastroenterologist/specialist.

- Patients with no/mild histological changes but confirmed autoimmunity should be followed closely.

In addition, the American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease recommends that in children younger than 2 years of age for CD, the IgA tTG test should be combined with deamidated gliadin peptide.

Autoantibody levels should always be tested while patients are taking a gluten-containing diet as the concentration of antibodies has been shown to disappear or fall to nearnegative levels within 12-18 months of strict adherence to a gluten-free diet. Although it is not possible to definitively correlate villus healing with the disappearance of serological markers, retesting of serology should occur at least at 6 and 12 months after diagnosis, and yearly thereafter, unless symptoms recur or there are complications.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our electronic Pathology Focus newsletter.

References

Elitsur, Y., Lawrence, Z. B., & Tolaymat, N. (2005, September). The Diagnostic Accuracy of Serologic Markers in Children with IBD: the West Virginia Experience. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology., 39(8), 670-673. doi:10.1097/01.mcg.0000173853.78-42.2d

Gower-Rousseau, C., Vasseur, F., Fumery, M., Savoye, G., Salleron, J., Dauchet, L., . . . Colombel, J. (2013, February). Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: New insights from a French population-based registry (EPIMAD). Digestive and Liver Disease, 45(2), 89-94. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2012.09.005

Kaplan, G. G., & Windsor, J. W. (2020). The four epidemiological stages in the global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology and Hepatology. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/ s41575-020-00360-x

Kelsen, J. R., & Sullivan, K. E. (2017, July 28). Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Primary Immunodeficiencies. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 17. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-017-0724-z

Kochhar, G., & Lashner, B. (2017, January 30). Utility of Biomarkers in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology, 15, 105–115. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-017-0129-z

Lamb, C. A., Kennedy, N. A., Raine, T., & et al. (2019, September 27). British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut, 68, s1-s106. Retrieved from http:// dx. doi. org/ 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484

Mulder, D. J., Noble, A. J., Justinich, C. J., & Duffin, J. M. (2014, May 1). A tale of two diseases: The history of inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis., 8(5), 341-348. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.009

Vegh., Z., & et al. (2014, November 1). EpiCom-group, Incidence and initial disease course of inflammatory bowel diseases in 2011 in Europe and Australia: Results of the 2011 ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis, 8(11), 1506-1515. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2014.06.004

Weimers, P., & Munkholm, P. (2018, January 23). The Natural History of IBD: Lessons Learned. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology, 16, 101–111. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-018-0173-3

Horwitz, A et al. “Screening for celiac disease in Danish adults.” Scand J Gastroenterol, 2015; 50(7): 824–831.

Husby, S et al. “European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2019.” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, (Ahead of Print).

Rubio-Tapia, A et al. “ACG Clinical Guidelines: Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease.” American Journal of Gastroenterology. 108(5):656–676, May 2013.

Caio, G et al. “Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review.” BMC medicine vol. 17,1 142. 23 Jul. 2019, doi:10.1186/s12916-019-1380-z