Surveillance trends and vaccine breakthroughs

By Dr Eric Chu

Published June 2025

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) is a highly contagious virus responsible for respiratory tract illness. While it causes a mild illness in most people, it is one of the most common causes of hospitalisation and death in newborns and infants. It is also a significant cause of mortality and morbidity among older adults with chronic health conditions. Consequently, it is a significant public health issue, with substantial research into preventing infection among vulnerable populations.

National surveillance: Identifying needs

While first identified in 1956, RSV has only recently been classified as a notifiable disease and was included in the Australian national surveillance program in July 2021 (Department of Health and Age Care 2025), with all states and territories contributing data since September 2022. Positive RSV cases are collected from all laboratory testing in Australia, including Australian Clinical Labs. In addition, hospitalisation and outcome data are collected from hospitals reporting to FluCAN, a respiratory illness surveillance network. The result has provided us with a clearer picture of the epidemiology and the burden of this disease in Australia, allowing for targeted intervention in those most at risk.

Australian epidemiological trends (2023–2024)

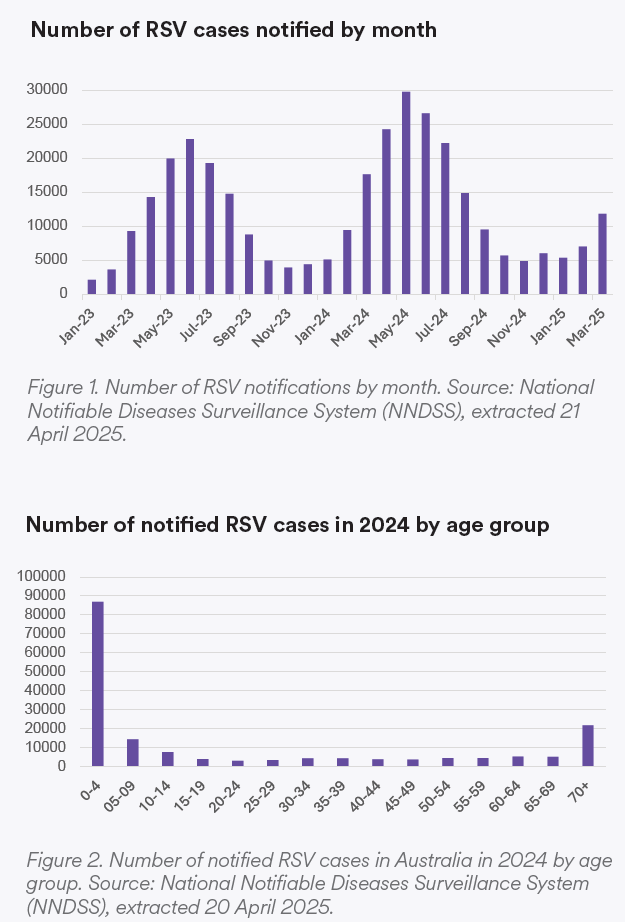

RSV season occurs from April to September in Australia, although variation can occur from year to year. It usually starts 1-2 months before the influenza season (see Figure 1). From 2023 to 2024, there was a 30% increase in notified cases, rising from 128,123 to 175,918 (Department of Health and Aged Care, 2025). Mortality involving RSV also increased from 363 to 462 between 2023 and 2024. 50%, 8.2%, and 12.4% of those cases occurred in the 0-4, 5-9, and over-70 age groups, respectively (see Figure 2).

Infants and children: The youngest at risk

In children, hospitalisation due to RSV is higher than for influenza and COVID (Department of Health and Aged Care 2025). Hospitalisation occurs overwhelmingly in infants and young children under 2. In this age group, 4.4% of hospitalisations require admission to ICU, and a small number of deaths have occurred. The risk factors for severe RSV in infants include any underlying cardiac or respiratory illness, immunocompromised conditions and preterm infants <32 weeks’ gestation.

Older adults: A growing concern

RSV is also increasingly recognised as a cause of illness and hospitalisation in older adults, particularly those with risk factors. In Australia, hospitalisation due to RSV in adults is lower than for influenza or COVID, but it has a similar rate of admission to ICU (8.5%) and mortality (4.3%) among those hospitalised. The risk factors predicting more severe diseases include underlying lung or cardiac diseases, including COPD, asthma and congestive heart disease. Other risk factors include diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease and immunocompromised adults. Among immunocompromised adults, the risk is highest for lung transplant patients or those who have had a haematopoietic cell transplant. Those undergoing chemotherapy for a haematological malignancy are also considered at higher risk.

Vaccine development

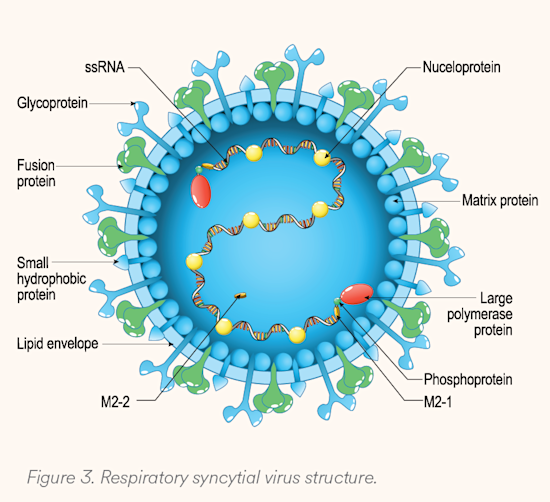

RSV contains eleven proteins (see Figure 3). Among these, two are responsible for viral infectivity, while also eliciting the most antigenic response. The fusion (F) protein is responsible for enabling entry of the virus into the host cell by fusing with the cell membrane, essential for viral function. The G protein is responsible for attachment of the virus to ciliated cells in the respiratory tract. There are two subtypes (A and B) for G proteins, making it a less ideal target for vaccines, as antibodies targeting the G protein may be subtype-specific, while those targeting the F protein should affect both subtypes. As understanding of these proteins and the pathogenesis of RSV has improved, vaccine development has also improved, leading to vaccines targeted to the F protein.

Palivizumab is a monoclonal antibody that was approved by the FDA in 1998, and the TGA in 2015. It targets the F protein; however, it was found to provide only modest effectiveness and would require monthly injections throughout the RSV season. Palivizumab is therefore generally considered an unrealistic option beyond hospital settings in those at the highest risk.

In 2011, a breakthrough occurred in the identification of two major structural conformations of the F protein: the known post-fusion (postF) and a pre-fusion (preF) form. The postF protein is more stable and subsequently identified as the target of palivizumab. The preF protein contains different antigenic sites and is found to be more vulnerable to neutralising antibodies. This led to the development of new vaccines, all targeting the preF protein, three of which have been approved for use in Australia since 2023. These are nirsevimab (Beyfortus), Abrysvo and Arexvy. There is also an mRNA vaccine, but it is not currently approved in Australia.

New vaccines

Nirsevimab (Beyfortus): For infants

Nirsevimab is a human recombinant monoclonal antibody. It has a longer half-life and 50-fold higher neutralising activity compared to palivizumab (Wilkins D 2024). In two phase 3 clinical trials, it demonstrated 83.2% vaccine effectiveness in protecting against infection and hospitalisation, first in at-risk infants (Drysdale S 2023). More importantly, in healthy late pre-term and term infants, the vaccine effectiveness is 74.5% (Hammitt L 2022).

It has replaced palivizumab as the vaccine of choice for infants. In addition to this, it is now recommended for all infants for their first RSV season. It maintains neutralising antibody levels for around 5 months; therefore, only one dose is required at the beginning of the RSV season.

Abrysvo: For pregnant women and older adults

This is a recombinant bivalent vaccine containing RSV preF protein subgroups A and B. This is the only vaccine available for pregnant women. Its efficacy was shown in a phase 3 randomised trial including 7,148 births (Kampmann B 2023). When compared to placebo in infants, it demonstrated a vaccine efficacy of 81.1% and 57.1% at 90 days after birth against severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI) and RSV-associated medical presentation respectively, with sustained efficacy of 69.4% and 51.3% at 180 days after birth. Another trial in older adults demonstrated 67% vaccine efficacy in preventing RSV-associated LRTI (Walsh EE 2023).

Arexvy: For older adults

This is monovalent adjuvanted RSV preF protein. Because it is an adjuvanted vaccine, it is potentially more immunogenic than Abrysvo, although no head-to-head studies have been performed. Clinical trials demonstrate vaccine efficacy of 82.6% when compared to placebo for confirmed RSV infection, and 94.1% for severe RSV-related LRTI (Papi A 2023). Despite being a monovalent vaccine, it is similarly effective against both RSV serogroups A and B.

Current immunisation recommendations

Given the number of new vaccines, the recommendations are complex. They are listed in Table 1.

Abrysvo in pregnant women is currently funded through the National Immunisation Program. Other vaccines may be funded through state programs, which vary; for example, nirsevimab is funded in some states.

Regarding vaccination in older adults, while vaccine efficacy decreases in subsequent years, current data suggests efficacy for at least two years. There is insufficient data beyond this, and it is unclear whether boosters will provide any additional benefits.

Table 1. Immunisation recommendations for RSV.

| Populations | Criteria | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnant women | All women between 28-36 weeks’ gestation. Should be given >2 weeks before birth but can be given after 36 weeks’ gestation. | Receive 1 dose of Abrysvo |

| Infants and children | < 8 months old going into first RSV season, and: • Born to a mother who did not receive the RSV vaccine or was born within 2 weeks of receiving the RSV vaccine; or • Mother is immunosuppressed and unlikely to mount immune response to RSV vaccine; or • Infants at risk for severe RSV disease 8-24 months going into their second RSV seasons: • Conditions at risk for severe RSV disease | Receive 1 dose of nirsevimab |

| Adults >60 years old | Conditions that increase risk of severe RSV disease | Arexvy or Abrysvo Not enough data on booster recommendation currently |

| Adults >75 years old | No exclusion criteria | Arexvy or Abrysvo Not enough data on booster recommendation currently |

Conclusion: Looking ahead

The recent progress in RSV immunisation represents a pivotal moment in respiratory disease prevention. The integration of these vaccines into routine immunisation schedules promises to significantly reduce the incidence and severity of RSV infections among the most vulnerable members of our population. Ongoing surveillance data, including vaccination data, will help us further assess the real-world efficacy of vaccines and the need for boosters in older adults, as well as identify any current gaps in vaccine coverage.

Improving the quality of surveillance and outcomes for RSV requires coordination among primary health care providers, laboratories, hospitals, and public health services to enable recognition and confirmation of cases through testing. It is the responsibility of every health care provider.

As we continue to monitor and refine our strategies, the hope is that we can further reduce the impact of RSV on vulnerable members of our society.

Respiratory Multiplex PCR Testing at Clinical Labs

Visit our Respiratory Testing pages for state-specific ordering instructions.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our electronic Pathology Focus newsletter.

Subscribe Today!

References

Department of Health and Aged Care. 2025. National notifiable disease surveillance dashboard. Accessed April 14, 2025. https://nindss.health.gov.au/pbi-dashboard/.

Department of Health and Aged Care. 2025. 2024 Annual Australian Respiratory Surveillance Report . Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Centre for Disease Control).

Drysdale S, Cathie K, Flamein F, et al. 2023. “Nirsevimab for Prevention of Hospitalizations Due to RSV in Infants.” NEJM 389:2425-2435.

Hammitt L, Dagan R, Yuan Y, et al. 2022. “Nirsevimab for Prevention of RSV in Healthy Late-Preterm and Term Infants.” NEJM 386:837-846.

Kampmann B, Madhi SA, Munjal I, et al. 2023. “Bivalent Prefusion F Vaccine in Pregnancy to Prevent RSV Illness in Infants.” NEJM 388:1451-1464.

Papi A, Ison MG, Langley JM et al. 2023. “Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F Protein Vaccin in Older Adults.” NEJM 288:595.

Ruckwardt, Tracy J. 2023. “The road to approved vaccines for respiratory syncytial virus.” npj Vaccines 8:138.

Walsh EE, Pérez Marc G, Zareba AM et al. 2023. “Efficacy and Safety of a Bivalent RSV Prefusion F Vaccine in Older Adults.” NEJM 288:1465-1477.

Wilkins D, Hamren U, Chang Y, et al. 2024. “RSV Neutralizing Antibodies Following Nirsevimab and Palivizumab Dosing.” Pediatrics 154:e2024067174.