By Dr Linda Dreyer

Published June 2021

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have burdened humans from the beginning of time, although we have all the means to manage and control STIs we are not keeping them at bay. In recent times we have seen a rise in infection rates, and even the re-emergence of some.

In countries where testing and antibiotics were readily available, very low levels of syphilis were detected in the 20th century. In 2010, only five new infections per 100,000 people were reported in Australia.

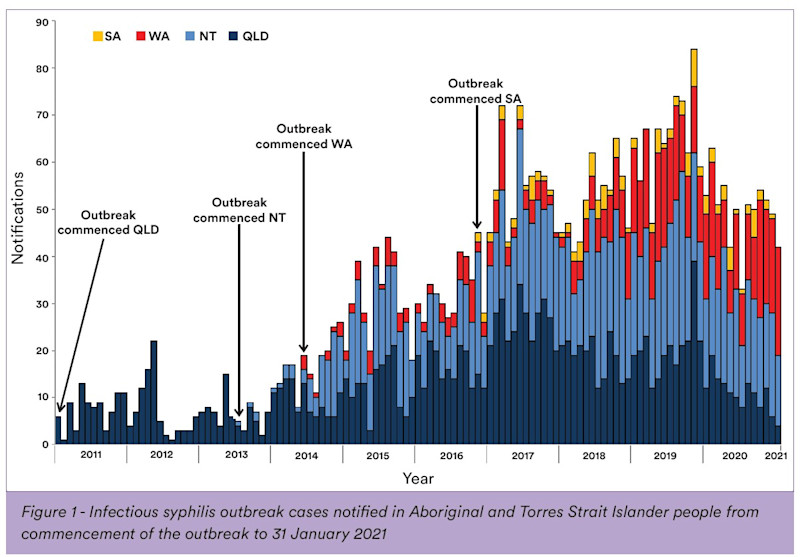

Unfortunately, rates of syphilis are increasing in high income countries across the globe. Data from the Kirby Institute showed that in 2018, there were 5,078 infectious syphilis notifications, 3,015 more notifications than in 2014 – an increase of 146%. A multi-jurisdictional outbreak of syphilis began in northwest Queensland in January 2011; from there it spread to the Northern Territory, then to Western Australia, and recently to South Australia.

In Victoria, the reported cases of syphilis increased from 635 cases in 2014 to 1,676 cases in 2019. The reduced testing during the COVID pandemic in 2020 was responsible for the small decrease in numbers with only 1,444 cases notified. This has also led to an increase in congenital syphilis, which is of great concern. This is caused by mother-to-child transmission of infection, andhas re-emerged in Victoria with 10 cases reported since 2017. In South Australia, seven cases of infectious syphilis have been detected in pregnant Aboriginal women since November 2016, and two cases of congenital syphilis were reported. Queensland had 20 cases of congenital syphilis notified from 2010 to 2020. In 2020, a total of 19 cases of congenital syphilis were reported in Australia; this number includes stillbirths.

Why is this a problem?

A baby can contract congenital syphilis through transplacental transmission from its mother. The transmission rate is highest (60% to 90%) during untreated primary and secondary syphilis. This decreases to approximately 40% in early latent syphilis and <10% in late latent syphilis.

Congenital syphilis can result in stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight, or neonatal death. A baby with congenital syphilis may present with early or late onset disease. They may appear normal at birth, but at 2 months will develop a range of clinical manifestations that include a variety of symptoms from skin lesions to organomegaly and bone, blood, and brain abnormalities.

Late onset disease is seen after 2 years of age, and this includes sight and hearing problems, bone and teeth malformations, and central nervous system abnormalities.

What can we do?

- All pregnant women should get a syphilis test during their first antenatal visit, as well as all pregnant patients who never received antenatal care and present for the first time late in pregnancy.

- All women presenting at any stage of pregnancy with clinical signs of any other sexually transmissible infection should get tested for syphilis.

- Repeat syphilis tests at 28 to 32 weeks of pregnancy, and at delivery, in all women at high risk of sexually transmissible infections.

- Repeat syphilis testing in all women from communities experiencing an outbreak of syphilis.

- If patient presents with a genital lesion, a swab for syphilis PCR as well as serology is recommended.

- Syphilis should be excluded in all sexually active patients presenting with a rash.

Image shows secondary stage syphilis "palmar" lesions on the palms of the hand.

Treatment of cases and contacts

Prompt treatment of a pregnant woman diagnosed with syphilis with long acting (benzathine) penicillin is recommended. Short acting formulations such as benzylpenicillin should not be used, because they are ineffective.

Make sure the patient is not lost to follow-up. Sexual contacts of women diagnosed with syphilis during pregnancy should be tested and treated. All babies born to mothers diagnosed with syphilis in pregnancy will require follow-up by a specialist paediatric clinic.

Conclusion

Syphilis is still a challenging disease to diagnose, and true to the name the “Great Imitator” may masquerade as a wide range of other medical conditions. Physicians must be aware of the increase in congenital infections and actively screen pregnant patients, not only at the first antenatal visit but more frequently when risk factors are present. To eliminate congenital syphilis, early case detection, appropriate treatment, and adequate follow-up of infected women, their babies, and their sexual partners is required.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our electronic Pathology Focus newsletter.

How to Order Syphilis Testing

Syphilis should be excluded in all sexually active patients presenting with a rash.

Complete the Clinical Labs general pathology request form, listing syphilis and any other required STIs.

If all recommended STIs for asymptomatic screening are required (gonorrhoea, chlamydia, syphilis, HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C), write “STI Screen” in the Clinical Notes.

If the patient presents with a genital lesion, a swab for syphilis PCR as well as serology is recommended.

If there is a clinical suspicion of primary syphilis but serology is negative, ensure a PCR swab has been completed and repeat serology after 2 weeks following presumptive treatment.

Bulk-billed, subject to Medicare eligibility criteria.

References

-

Sixth child dies from congenital syphilis in northern Australia BMJ 2018; 360 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1272 (Published 19 March 2018)Cite this as: BMJ 2018;360:k1272

-

Syphilis dramatically on the rise in Victoria: Report https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/syphilis-dramatically-on-the-rise-in-victoria-repo

-

https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/Infectious/Reports/Publications/sti/nsw-sti-update-jan-june-2020.pdf

-

https://www2.health.vic.gov.au/about/news-and-events/healthalerts/congenital-syphilis