The issue of iron deficiency in women

By Associate Professor Chris Barnes

Published June 2021

Iron deficiency is the most common cause for anaemia across all populations and is estimated to affect up to 2 billion worldwide.1 Patients presenting with iron deficiency is a common diagnostic and management problem, and iron deficiency in females is particularly common due to the increased iron requirements associated with menstruation and pregnancy.

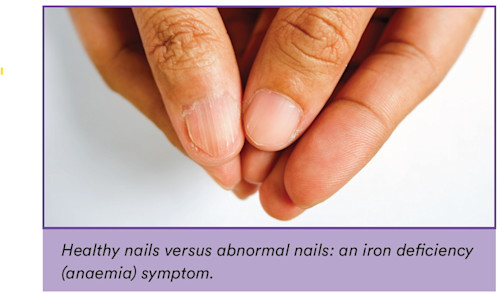

Symptoms of iron deficiency

Iron is essential to several biological functions, including energy production via mitochondrial metabolism, enzymatic processes involving neurotransmitters, and skeletal and cardiac muscle, and immune-based processes. This is in addition to haemoglobin mediated delivery of oxygen. This explains the common and varied symptoms associated with iron deficiency including lethargy, fatigue, brain fog (occasionally described misogynistically as “mummy brain”), restless legs, pica, and hair loss. These symptoms of iron deficiency occur prior to the development of iron deficiency anaemia, because iron stores are depleted initially from the liver and then from other iron enzymes and proteins in order to preserve erythropoiesis.

Iron deficiency anaemia will develop gradually over time, and patients may present with marked anaemia as low as 30 g/L. Whilst physiological compensation may occur, patients with marked iron deficiency anaemia may be at risk of cardiovascular instability including heart failure.

The impact of menorrhagia on iron levels

The most common risk factor associated with iron deficiency in females is menorrhagia. Whilst the average age at menarche is 13.8 years, menarche as early as 9 years may be considered normal and is influenced by both genetic and nutritional factors. The volume of menstrual blood loss may be difficult to accurately assess. Functional measures including asking about the passing of large clots, the need for double menstrual products to avoid flooding, the need to change products overnight, or concern about flooding during the day can all be used to assess for the presence of menorrhagia.2

Benefits of iron studies in diagnosing iron deficiency

Laboratory tests to screen for iron deficiency in female patients can be helpful as a part of good clinical practice even in the absence of symptoms of menorrhagia. Anaemia secondary to iron deficiency can be identified in up to 18% of otherwise healthy women, whereas iron deficiency (in the absence of anaemia) was present in 48% of 271 “asymptomatic” women participating in acommunity running event.3

A complete assessment of iron studies is recommended as an important first step in the investigation of patients with potential iron deficiency. Whilst an isolated low serum ferritin test is an adequate test if the patient is otherwise well, it is well known that ferritin is an acute phase reactant and may be falsely elevated in acute and chronic inflammation, fatty liver, raised BMI, or in the setting of OCP use. Additional laboratory markers available when ordering iron studies may be helpful in the assessmentof iron deficiency; a low transferrin saturation (<20%)supports a diagnosis of iron deficiency in patients with concomitant inflammation or systemic illnesses (even in the presence of a normal serum ferritin).

Below is a table to assist in the interpretation of iron studies in females presenting with risk factors or symptoms suggestive of iron deficiency.

| Iron | Transferrin saturation | Ferritin | Soluble transferrin receptor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron deficiency | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased | Increased |

| Iron deficiency + acute phase response | Decreased | Normal or decreased | “Normal” <100μg/L | Increased |

| Acute phase response | Decreased | Decreased | Increased | Normal |

| Iron overload | Increased | Increased | Increased | Decreased |

Clinical Labs' iron studies reference ranges

The table below details the reference ranges for Clinical Labs iron studies testing for female patients.

| TEST | GENDER | AGE | LOWER LIMIT | UPPER LIMIT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRON SERUM | F & M | All | 10 | 30 |

| TRANSFERRIN | F & M | All | 2.1 | 3.8 |

| IRON SATURATION | F | All | 15 | 45 |

| FERRITIN SERUM | F & M | 6m - 15 years | 20 | 140 |

| FERRITIN SERUM | F | 15 - 50 years | 30 | 200 |

| FERRITIN SERUM | F | >50 years | 30 | 300 |

Treatment

Treatment of iron deficiency should focus on the underlying cause including consideration of any sources of bleedingincluding menorrhagia, polymenorrhoea, or occult gastrointestinal blood loss. Iron supplementation in either oral or parenteral form is required after sources of blood loss have been addressed.

Oral iron supplementation may be associated with a high risk of gastrointestinal symptoms including nausea and abdominal pain. Second daily oral iron supplementation may reduce the incidence of the effects and may be associated with improvement in hepcidin-mediated iron absorption.4

Parenteral iron therapy has the potential to rapidly increase iron stores and with the availability of parenteral preparations that are associated with less risk of acute reactions, are an acceptable and attractive alternative to consider in females presenting with iron deficiency.5

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to our electronic Pathology Focus newsletter.

Subscribe Today!

References

-

Camaschella C. Iron-Deficiency Anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):485-6.

-

Fraser IS, Mansour D, Breymann C, Hoffman C, Mezzacasa A, Petraglia F. Prevalence of heavy menstrual bleeding and experiences of affected women in a European patient survey. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128(3):196-200.

-

Dugan C, MacLean B, Cabolis K, Abeysiri S, Khong A, Sajic M, et al. The misogyny of iron deficiency. Anaesthesia. 2021;76 Suppl 4:56-62.

-

Stoffel NU, Zeder C, Brittenham GM, Moretti D, Zimmermann MB. Iron absorption from supplements is greater with alternate day than with consecutive day dosing in iron-deficient anemic women. Haematologica. 2020;105(5):1232-9.

-

LaVallee C, Cronin P, Bansal I, Kwong WJ, Boccia R. Importance of Initial Complete Parenteral Iron Repletion on Hemoglobin Level Normalization and Health Care Resource Utilization: A Retrospective Analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39(10):983-93.